With courtesy of Cedric Briand

My husband and I have had a rough few weeks, so yesterday, we decided to take a little adventure to Northfield, MN by way of Cannon Falls. We ultimately ended up at Tanzenwald Brewing Company, a great space with a schnitzel-sandwich concoction which I ate in an uncomfortable, “oh yeah I guess I really am German” kind of way.

As we entered, I saw and heard a person sitting on a djembe playing a repetitive yet intricate rhythm. I hadn’t heard what came before, so I didn’t have context to understand it musically, but it was soothing and comforting. My stress level has been high, so some fried pork and centering music was welcome.

I pulled out my phone, as one does, seeking more information about the music. Greenvale Manitou is the musical project of Cedric Briand. Like the obsessive I am, I went straight to the “About” page of their site. Briand writes:

I believe that what connects us all musically lies in the urge most of our ancestors have had to stretch the skin of an animal on a carved piece of wood at one point or another.

I have spent the last academic year developing a new music history curriculum for Augsburg University. Greenvale Manitou’s statement could well sum up the two semester sequence of “Music and Identity in the Americas” and “Musical Philosophy.” “What connects us all musically” is roughly where we started and, after a marathon of conversations, explorations, conflicts, and hopefully introspection, it’s roughly where we are ending up this week, the last week of classes.

Suddenly, I had schnitzel, beer, and a lesson plan. Not bad for a Saturday.

Of the recent song, “Born of the Same,” Greenvale Manitou asserts:

The song incorporates British sounding rock guitars, elements of dream rock, produced modern hip-hop, ambient samples, and acoustic percussion.

Harmonically, the song simply oscillates between two poles, with notable deviations that, nevertheless, do not disrupt a sense of presence without the obligation of a goal-oriented progression. We aren’t going anywhere in particular if we look at harmonies. But through rhythm, timbre, and texture, we are.

In the Western Art Music canon, European and American music in the tradition of Bach and Beethoven, going somewhere is incredibly important. In the 19th century, my discipline of musicology all but eviscerated academic study of musical elements other than harmony. When music students write Roman numerals under chords in their music theory homework, they are commenting almost exclusively on harmonic progression.

My discipline, my schnitzel, and my beer are all implicated in that. If you don’t spend your days fretting over the nationalist and racist implications of how the academic study of music emerged as, at least in part, a concerted effort to center and privilege a fictional German-ness in the mid 1800s, that’s probably not a big deal. It’s my job, however. I was specifically tasked with helping my students understand these uncomfortable ideas while not denigrating the Classical tradition. Some of my colleagues (across institutions) are understandably skeptical that it can be done or, maybe more to the point, that it should be done.

Looking back on the 2023-2024 academic year, I think we’ve managed it pretty well. There have been hiccups, but my students learned about Beethoven in a way that, I hope, valued his work without making him a deity. That required me to not pretend to be a sage of all things music, to not use a textbook, and, to the best of my ability, to be malleable.

The kind of fusion Greenvale Manitou engages is facilitated by a de-centering of a sonic narrative that music academia has struggled for decades to challenge: teleological harmonic language. That’s the stuffy terminology, derived from a parallel and also troubling intellectual narrative, that I use in class. But it just means “goal-oriented.”

The Ethics Center describes teleology as “an explanation of something that refers to its end, purpose or goal.”

Greenvale Manitou has a clear purpose. The music’s structure, though, doesn’t privilege the end. It privileges the present. Many musicologists and ethnomusicologists have used this philosophical lens to understand varied musical practices. In many traditions, sound is used to build community, reinforce social bonds, and explore collective obligations. That is often reflected in the musical content, which is frequently “non-teleological.”

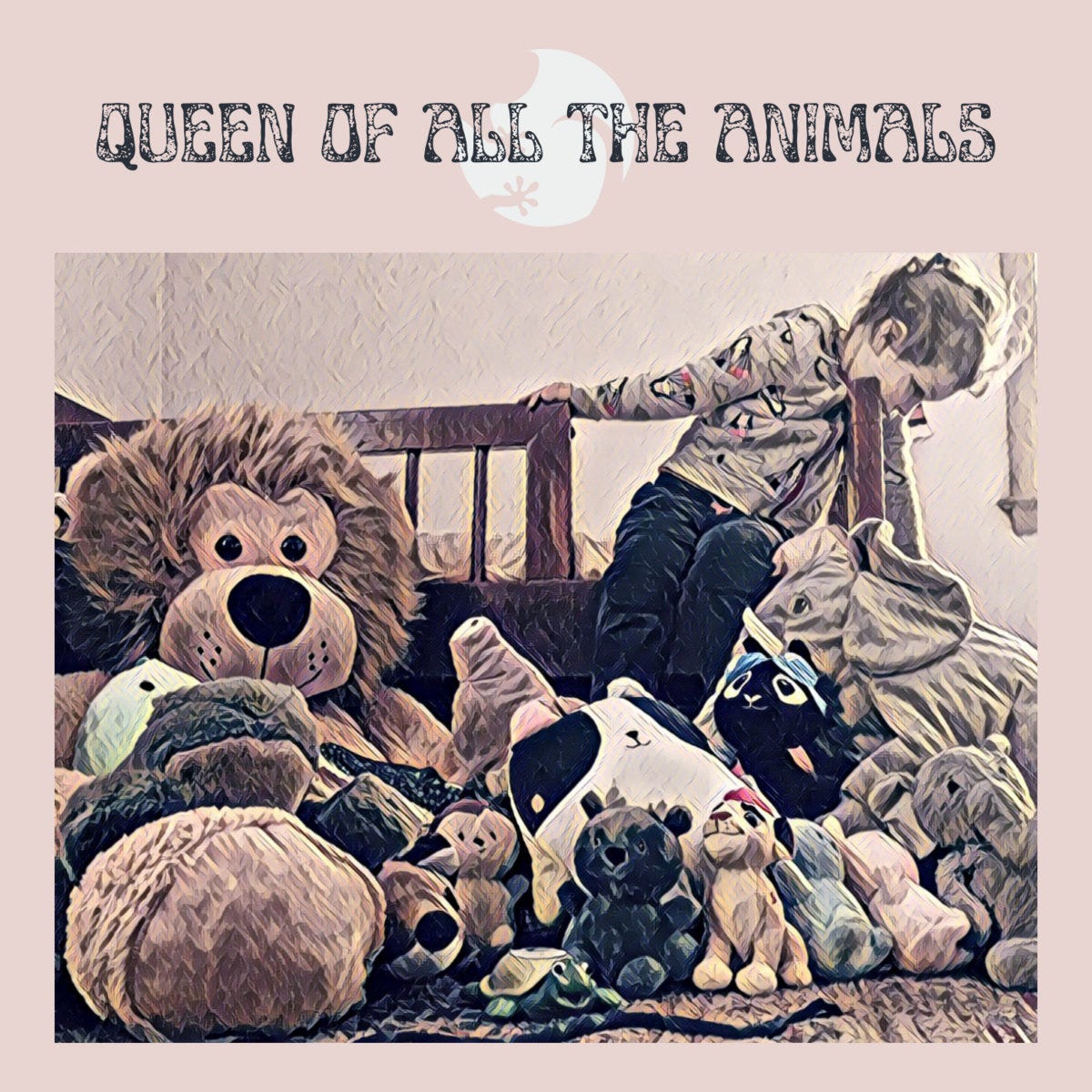

Greenvale Manitou provides behind-the-scenes videos demonstrating their production process. In this video, they are working on “Queen of All the Animals.” They layer sounds, and with them genres and traditions, joyfully but carefully. They are focused on the texture and timbre, not so much on harmonic progression.

So, a lesson plan emerges.

I was curious about the name. I know what a Manitou is, at least in broad strokes. Merriam-Webster gives us this: “a supernatural force that according to an Algonquian conception pervades the natural world.” The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary provides manidoo: “a manitou, a spirit, god.”

I wondered how European-American composers might reference the concept. After all, it must have been an appealing notion to the Romantic composers trying to work out an American “classical” tradition in the 19th century. It’s logical that, like their European counterparts, they would look to mysticism, “folk” culture, and polytheism as ways to define the nation. The drug-induced hallucinations of Berlioz or Wagner’s Teutonic, anti-semitic paganism wouldn’t be sufficient. They felt a compulsion to lay claim to their own land. As they genocidally stole the land from the people who had it first, as all imperialists do, they appropriated pre-existing cultural markers in service of creating a distinct nation in their own image.

A little googling brought me “Manitou Mysteries,” a symphonic work by a composer I had never heard of, Anthony Philip Heinrich, “the American Beethoven.” That I’ve never heard of him and I’m guessing you’ve never heard of him indicates the absurdity of thinking that tacking a bit of local flavor on top of a European musical tradition would amount to American Music.

I actually really like the little of Heinrich’s music I’ve listened to. It’s kind of weird, as I expected. It’s also teleological, as he had been taught to compose.

My actual opinion of this particular composer will take more time to work out, but I find it interesting to juxtapose these two references to an Algonquin cultural system, with what I perceive to be two different underlying impulses.

This is where some teacher or professor from my past runs to me in a panic and says, “Kevin, stop calling all Classical music racist!” To which I calmly reply, “please re-read the text.”

Tanzenwald Brewing Company, where I got my schnitzel, is just down the street from Greenvale Ave. I assumed that’s where the Greenvale of Greenvale Manitou came from. I googled anyway and discovered Greenvale Place, an affordable housing community a few blocks away. I don’t know if that’s the reference (I’ll ask when I get a chance), but it was what appeared on my phone as I listened to Briand create rhythmic and melodic patterns that helped me, for a moment, enjoy a beer without the crushing weight of calculating mortgage payments and contending with the hypocrisy of complaining about them.

Augsburg, Heinrich, affordable housing, Algonquin spirituality, schnitzel, and beer are all elements of the context within which I heard and continue to hear Greenvale Manitou. Context is undervalued in the academic study of music. I need my students to value it. That way, the new music history curriculum at Augsburg can work. In cultural studies, adding things does not require eliminating things. We just need context, critical thinking, and compassion.

And to not believe teleological art is superior to other art.

Greenvale Manitou’s “Queen of All the Animals” is dedicated to Briand’s daughter. I don’t have children, but I’m at an age where I once had a student in a college classroom who had been in my preschool classroom 20 years earlier. So, I tend to think of children as possibly, eventually being students. I look forward to discussing teleology with her. That was a pretty teleological statement.