My Grandfather died a decade and a half before I was born. He died of a combination of stress, cigarettes, and some condition that can only be pseudo-diagnosed posthumously by my cousin, a physician assistant, from photographs. All four of my grandparents sit obtrusively but indispensably in my brain, assessing and evaluating me, directing my perceptions, and shaping my choices. But the one I never met is paradoxically the loudest and the most intuitive. Most days, he’s the one I relate to the most and the one who would probably understand why I do things I know are not good for me.

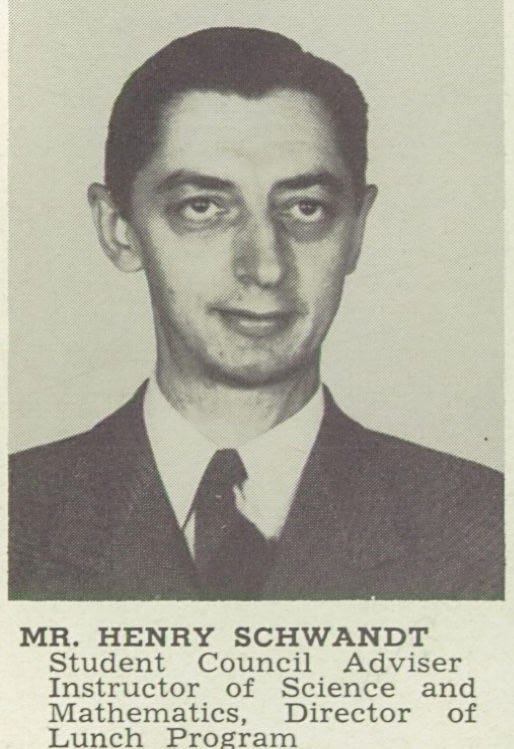

We share a middle name. I’ve always been puzzled by that. In some families, a grandparent’s first name is a likely choice for a child’s middle name. Neither “Henry,” his first name, nor “Carl,” his middle name, are particularly exotic or exciting. “Carl” takes less time to say, I suppose, and it is alliterative with my first name, so when adults in my life were angry with me, a sharp “Kevin Carl!” hit harder than “Kevin Henry!” would have. It makes sense.

I wonder if his parents yelled “Henry Carl!” when he belligerently read a book rather than engaging in social activities or forgot to clean the windows because he was thinking about something else. His name claims the same number of syllables as my rebukes but without the alliteration. His “H” is soft; my “K” is jagged and reinforced by the subsequent hard “C.” A double punch.

We share a last name and the same number of syllables in the overall nomenclature, so naming me is similar to naming him, just with that violent, biting consonant at the outset. We are both Carl.

In the years when “Kevin CarI!” was a refrain in my life, I was very much living in Henry Carl’s world. I was raised in his school district, the district he briefly served as superintendent before the cigarettes and stress and mystery ailment put the kibosh on that whole situation while concurrently tossing my teenaged father’s still developing brain, along with his sister’s slightly more developed but still unfairly young brain, into a trauma blender.

Henry was an educator in the 1960s, a period of massive change in everything in American culture, but probably most significantly for him, in education. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act was signed into law in 1965. My Grandpa, superintendent of my school district, died the next year.

Finding himself at the helm of one of the ships traversing that mess, I wonder if he felt chest pain. I wonder if he would know his grandson would be approaching his terminal age still trying to hold those boats together while also feeling physical discomfort and seeking chemicals to make the general public’s disregard and disrespect of the voyage hurt less.

I don’t know why he did this or why I continue to do this. There’s not much to recommend about a life in education. It’s a lot of giving people things they don’t want and won’t thank you for because the alternative is unthinkable. I’m not referring to students, here. Students thank me a lot. It’s everyone else who doesn’t particularly care about what Henry or Kevin or a zillion other people do. Or our chest pain.

For a few months in high school, I tried to get people to refer to me as “K.C.” It was very stupid. Somehow, I wanted his name to be in my name. When adults yelled “Kevin Carl!” at me, they inadvertently summoned Grandpa. He was welcome company, so I also wanted him with me when I wasn’t in trouble.

He was on the front lines of Title I when it was a brand new thing. His last year of life was likely a constant assault of people who were not teachers yelling at him about how teaching should be. It was also probably a constant assault by teachers who felt abused by a system telling them to do something different. He wouldn’t have taken the job that killed him if he didn’t think it was the right thing to do.

We still don’t have equitable education. I’m still being told what to do by people who don’t know what I do. My middle name is my middle name, so I’ll keep listening to people yell “Kevin Carl!” I wish I had that gentler “H,” though.