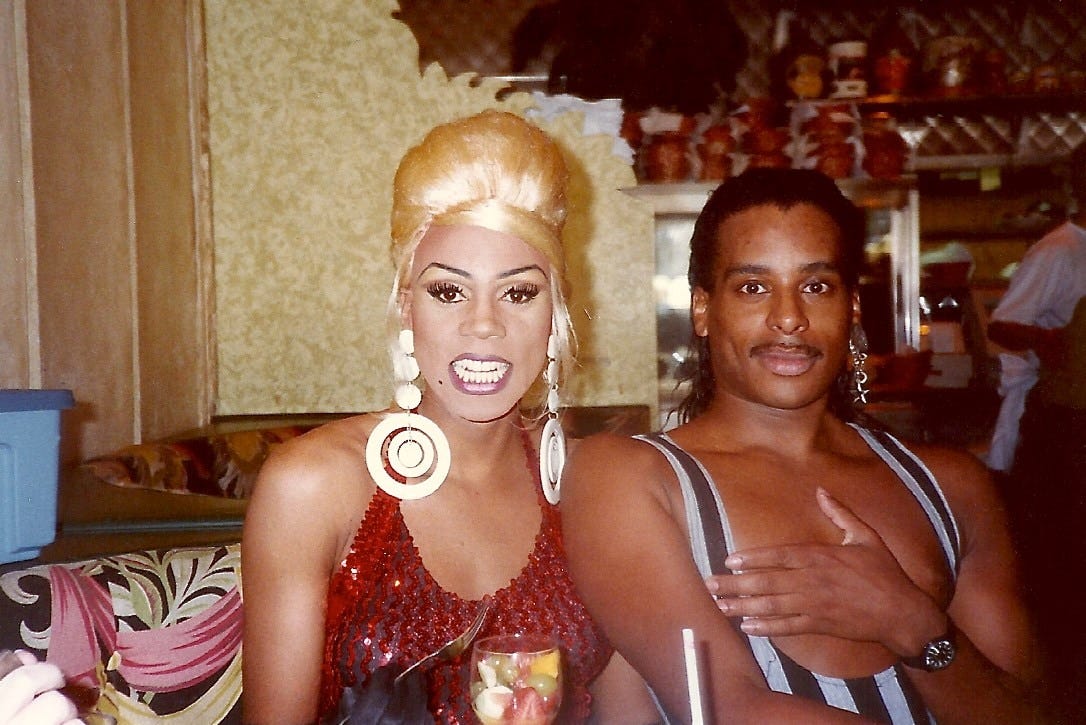

I gave the drag queen a $20 bill, and she said, “Ooh, you’re rich.”

“No,” I replied. “Just grateful.”

I’m guessing she was half my age, but when she said she was a teacher by day, our generational distance shrunk. We talked about our husbands a little, enough to realize that we were both able to be artists because we married businessmen. We talked about our students and our art.

I explained that the last time my husband and I had been in this dark, sticky bar was 15 years ago.

My husband kept telling people about the sweatshirts we bought back then, which wouldn’t possibly fit on my body anymore.

“Do they still have the sweatshirts?”

She shrugged. Not her job.

I told her that I, too, once upon a time, hosted a weekly RuPaul’s Drag Race watch party in a gay bar, back when the show was new and its first winner was from Minnesota. It was a long time ago and RuPaul was kind of old even then. She laughed, and I realized she probably didn’t have memories of RuPaul in the 1990s. Or the 1980s.

***

A few weeks ago, music historian Ted Gioia published excerpts from his journal, including a cutting assessment of the language used by musicologists and art critics: “The same adjectives used to describe fascist dictators are now terms of praise applied to paintings and songs and stories.” Parodying the snobby old academic music rhetoric he and I both know so well, he wrote: “Back in the day of the twelve-tone row, the trains ran on time…”1

Gioia knows, as I do, that Arnold Schoenberg—the man considered to be the father of the twelve-tone method, the antecedent to musical serialism—fled Europe in 1933. He lived in LA. Had he stayed in Berlin where he was living at the time, labeled a “degenerate” making “degenerate” art, he would certainly have been murdered before starting to write music that less strictly adhered to the serialist orthodoxy he had initiated. That later music includes A Survivor from Warsaw, which Milan Kundera refers to as “the greatest monument music ever dedicated to the Holocaust.”2

Catastrophe and exile perhaps made Schoenberg rethink the standardization of his art. He recalled that there was more to music than systems and math and form.

In A Survivor from Warsaw, the baritone narrator, laying on the ground after having been beaten unconscious, deliriously hears Nazis demanding a roll call to determine how many people they would send to the gas chamber, delineating the living from the dead. As the roll call begins, slowly at first but speeding up frantically, dissonant orchestral collisions building and accelerating toward apocalypse, the narrator hears the voices of the Warsaw Ghetto, “finally sounding like a stampede of wild horses,” manifested musically, as a chorus begins singing Shema Yisrael:

Hear, O Israel:

The Lord is God, the Lord is one.

[. . .]

And thou shalt teach them diligently

unto thy children,

And shalt talk of them when thou sittest

in thine house,

And when thou

walkest by the way,

And when thou liest down,

And when thou risest up.

When thou liest down. And when thou risest up.

I once showed my students a clip of Karlheinz Stockhausen, one of the composers who shaped Schoenberg’s serialism into its most rigid form—dehumanizing it, some might say—answering questions after a lecture in London in the early 1970s. In the clip, a student asks Stockhausen if he is concerned that normal people don’t understand his music. Stockhausen then articulates his apparent view that certain people are intellectually and aesthetically superior. His music, he asserts, is for them.

In London. In the 1970s. With his name.

Schoenberg had once articulated and enforced a similar aesthetic elitism. Then things happened. He remained elitist, to be sure, but horrendous loss, unthinkable suffering, and the apocalyptic consequences of bigotry softened his dogmatic intransigence.

Many of my students didn’t understand why I showed them that clip of Stockhausen, a composer whose music I detest. It was just a weird German dude being rude to a British college student. As a weird German dude, I thought I had an obligation:

“Because you are artists. What you do and how you do it has power. Who are you singing for?” I said, trying to express a sentiment never uttered by the weird German dude who is the current President of the United States.

The first time a student admitted to me they used AI to write a paper, my second thought was, How are you going to know when you’re lied to? My first thought was, Shit, I’m going to have to fail this kid. I didn’t fail the student. We talked and worked out a solution. I hope the student understood that my second thought was the important one. My first thought was self-centered.

I’ve seen too many people excited by the prospect of giving up their distinctiveness, their power.

The total serialists like Stockhausen were (are?) driven by certain impulses. As I am not a total serialist, I am admittedly speculating a bit. After World War II, academic music in the West took a fairly hard turn toward math, systemization. Much of society took a hard turn toward math, so coupled with what I think is a general self-consciousness and anxiety among many musicians in universities, it isn’t surprising, exactly.

But there was more to it. This drive to systematize, rationalize, and quantify coincided with enormous leaps in recording technology. Computer music emerged. With computers, composers could begin to eliminate the need for performers. Performers can be imperfect. Human. Computers play no wrong notes.

Schoenberg had developed twelve-tone music, or serialism, to be a liberation of dissonance, a new language to help musicians (certain, approved musicians) to break free from the old language. He described musical operations that could be expressed mathematically using base-12 arithmetic rather than the tonal relationships that had structured European music for several centuries.

The total serialists like Stockhausen built upon Schoenberg’s principles, developing formulas, creating logical, rational operations that may be outside human capacity to perform, with the goal of serializing every possible aspect of sound. Computers provided a means, enabling a direct line from composer’s conception to sound, skipping the inconvenient middle stage: the human performer. The composer could exercise total control over sound, master the most abstract, nonrepresentational art form without pesky human collaboration.

Nothing wrong with that, I suppose. Artists should use the tools available to them. I’m not a Stockhausen fan, but perhaps I don’t have the innate, superior qualities he believed were required to understand his art. Despite my last name and its seven consonants and one vowel.

Yet, every day I read a new think-piece about how we are losing human connection, becoming uniform, desensitized, alienated, asocial. Art requiring alienation isn’t interesting to me at the moment. I desire connection.

The ancient Greeks believed music to be deeply embodied, but also deeply connected to the natural world, even the heavens. It was the vibrating glue that held communities and weather patterns and human health and animal behaviors together in harmony. Variations on that theme permeate the subsequent millennia of Western musical thinking. You can find the same throughout the musical traditions of the world. Where there is sound, there is music and a creation story. Where there is music, there is community and cohesion.

Schoenberg, the patriarch of serialism, never abandoned it, but his later music indicates to me that he thought about its implications. In the middle of the 20th Century, the world saw the effects of people with power seeking to eliminate difference, to restrict thought, to reduce human connection. To systematize. In the face of such horror, he turned to the Shema. He called out to hear and to be heard. He asserted his faith and his humanity.

My college students have started asking me to read their poetry. I teach them how to write research papers. They want to write poetry. Ten years ago, nobody asked me to read their poetry.

I think it’s because my students now know about loss. They know it differently than I did when I learned to play Schoenberg’s Opus 11, which he wrote in 1909, before some things happened. My students have lost a lot, though. More accurately, people have stolen a lot from them.

Kundera, referencing A Survivor from Warsaw, laments how we remember losses and injustices: “People fight to ensure that the murderers should not be forgotten. But Schoenberg they forget.”3

I noticed that my new friend, the queen emceeing Drag Race in a bar in Atlanta in 2025, left through the back door. I hoped there was a parking lot out back that we just didn’t know about. Maybe she was cutting through the alley. Maybe the back door was simply along the logical route for her commute home. I’m sure it was.

We stayed a while, remembering the space from back when we were young. It had probably been the fifth gay bar we’d visited the night we bought those sweatshirts. We only have one bar per night in us these days. I didn’t like the new sweatshirts, and I’d lost the body the old one fit on, anyway. The VJ played a clip of Willi Ninja voguing in the early 1990s. My husband and I watched Ninja’s artistry before leaving to go to the hotel. We went out the front door.

I have been physically attacked four times in my life. I’ve never been harmed by a drag queen. I’ve never been harmed by a queer punk or a nonbinary youth or a transgender woman. I’ve never been harmed by a dancer or a bouncer or a shirtless bartender.

I’ve been harmed by straight men lurking outside a gay bar, though.

As my husband and I walked to the car, I thought about degeneracy and gratitude. I also thought about the old bar in St. Paul, MN, where I used to host watch parties. It once had blacked-out windows. Decades ago, the windows were cleared off.

Decades ago, we stopped hiding our un-systematic selves.

As the US Administration and the cultural forces that support it continue their hunt for “degenerates” and free thinkers, caregivers and educators, migrants and downtrodden, we must keep making art that happens in sticky bars and public parks, concert halls and messy garages. It will be hard, but we must resist the temptation to become operators in a formula.

May we resist uniformity. May we never become standardized.

I do not have Schoenberg’s religion to turn to in trying times, so I sometimes turn to one of my own prayers, taken from the Creed of the legendary drag House of Aviance, fellow weird German dude Max Ehrmann’s “Desiderata.” To my new friend:

“You are a child of the universe, no less than the trees and the stars; you have a right to be here.”4

Gioia, Ted, “More Entries from My Private Journal,” The Honest Broker, 23 March 2025. https://www.honest-broker.com/p/more-entries-from-my-private-journal

Kundera, Milan, “Forgetting Schoenberg,” in Encounter, trans. Linda Asher (New York: Harper, 2009), 122.

Ibid.

Ehrmann, Max, “Desiderata,” in The Poems of Max Ehrmann, ed. Bertha K. Ehrmann. (Boston: Crescendo, 1948).

This is wonderful! Thoroughly enjoyed.